Focus – Summer 2025 edition

Published:Welcome to the Spring/Summer 2025 edition of Focus.

Introduction

In this edition, Singapore partner and Head of Asia, Fiona Gulliford and Washington DC associate, Sonia Forcada, explore “blue finance” trends in Latin America and Asia-Pacific.

Paris partner, Pierre Bernheim, and senior associate, Alexis Giroulet, look at the electricity law developments in the DRC.

In April, a cross-regional team of Stéphane Brabant (Senior Partner, Paris), Lucien Bou Chaaya (Global Head of Extractive Industries, Dubai), Adekanmi Lawson (Counsel, London) and Fiona Gulliford (Head of Asia-Pacific, Singapore) embarked on a visit to Shanghai and Beijing. Read their trip report below.

News

Trinity’s London office continues to strengthen its global disputes practice. Having welcomed James Dingley as a partner earlier this year, the team has now been joined by senior associates Pietro Bombonato and Ben Ainsley Gill.

Pietro joins Trinity from Omnia Strategy. He is a dual qualified lawyer (England & Wales and Italy) and a disputes specialist. In his professional practice, he has regularly been instructed by States and multinational corporations in international arbitration (treaty-based and commercial) and litigation proceedings. His instructions have spanned a variety of sectors including media and telecommunication, financial services, insurance, mining, agriculture, advertising and sports with a particular connection to Eastern Europe and the wider CIS region, Africa and the Middle East.

Ben is an English-qualified arbitration specialist with experience of commercial and investment disputes across a range of sectors under the principal arbitral rules, applying both common and civil laws. His disputes experience includes energy and infrastructure, construction mega-projects, real estate and commodities. Prior to joining Trinity, Ben also gained valuable in-house experience with a French multi-national.

Trinity’s London disputes team is able to assist Trinity’s clients across all aspects of contentious matters (arbitration and English litigation). The team is working on several sizeable instructions in respect of disputes in a wide range of jurisdictions and continues to work closely with the transactional practice advising clients in relation to a variety of investments in the energy sector across Africa.

Deal News

Since the last edition of Focus, we are proud to have been recognised in a number of industry awards:

At the IJ Global Awards, Europe and Africa held in London on 5 March 2025:

- Legal Adviser of the Year (Africa)

- Power Deal of the Year (Africa) – Nant Energy CCGT Plant, Sierra Leone

At the IFLR Africa Awards held in Cape Town on 7 March 2025:

- Francophone Africa International Firm of the Year

- Deal of the Year (Loans) – CrossBoundary Energy Financing

- Deal of the Year (Projects) – Western Area Power Generation Project: Sierra Leone

We are also proud to have advised on the following transactions in recent months:

- The African Trade & Investment Development Insurance (ATIDI), a long-standing client of Trinity in connection with the structuring and implementation of ATIDI’s Regional Liquidity Support Facility (RLSF), successfully finalised its latest RLSF agreement during the Africa Energy Forum. The agreement will support Globeleq’s 35 MW Menengai Geothermal Project in Kenya, and is the first ever RLSF policy in Kenya and the first for a geothermal project. Once operational, Menengai will deliver clean, reliable power to Kenya’s grid. To date, ATIDI’s RLSF has supported 9 projects across 4 countries, enabling 181.95 MW and mobilizing USD323.7 million in financing. The Trinity team advising ATIDI included partner Jo Sykes, and associate Rhiannon Lock.

- Globeleq in relation to a share purchase agreement (signed on 19 June 2025) with Norfund, for the proposed acquisition of a 51% equity stake in the Zambian entity, Lunsemfwa Hydro Power Company Limited (LHPC). LHPC operates two hydroelectric power plants totalling 56MW and is constructing a 20MW solar PV project. The remaining 49% of LHPC is owned by Wanda Gorge Investments, a Zambian based infrastructure investment company.

Africa Energy Forum (AEF)

The Trinity team, including representatives from our London, Paris and Singapore offices, attended the Africa Energy Forum in Cape Town in June. The conference was, as ever, very well attended and provided a great opportunity to catch up with friends and colleagues working on sustainable development and impact finance transactions across the African continent. We were delighted to welcome over 300 of our clients to our party on the Tuesday evening, to thank them for their ongoing support and celebrate their numerous achievements over the past year.

Office moves

Finally, both our London and Washington DC offices have moved! You can now find us at:

63 Queen Victoria St, London EC4N 4UA

and

1025 Thomas Jefferson St. NW, Suite 400 West, Washington, D.C. 20007.

***

Blue Bonds in Emerging Markets: Trends in Latin America and Asia-Pacific

Introduction

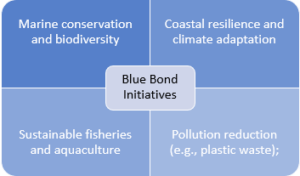

Blue bonds are a type of sustainability bond specifically designed to finance marine and ocean-based projects that support the blue economy—a sustainable use of ocean resources for economic growth, improved livelihoods, and ocean ecosystem health and comprise initiatives such as reduction of ocean plastic pollution, marine ecosystem restoration, sustainable shipping, eco-friendly tourism, or offshore renewable energy[1].

Projects financed by blue bonds are aligned with related Sustainable Development Goals (“SDGs”), including SDG 14: Life Below Water, and often also with SDG 6: Clean Water and Sanitation. To meet these goals, blue bonds must have clear environmental objectives, track how funds are used, and report on use-of-proceeds[2].

Currently, there is no dedicated regulatory framework for blue bonds. In practice, most of these instruments follow The International Capital Market Association (“ICMA”) Green Bond Principles, with adjustments to reflect the specific needs of ocean-focused investments[3]. As interest for these instruments grows, market actors are requesting clearer definitions, additional guidelines, and legal frameworks to help scale blue finance. Even though the regulatory framework is still taking shape, Latin America has become a leader in blue bond activity. The region is well positioned to do so: over 25% of the population lives near the coast and marine territory often exceeds landmass. The oceans play a key role in local economies through tourism, shipping, aquaculture, and fishing, and act as natural buffers against climate change[4]. But these ecosystems face increasing pressure from overuse and pollution. In response, countries across the region have launched a series of innovative blue finance transactions. These deals, often supported by Multilateral Development Banks (“MDBs”) and Development Finance Institutions (“DFIs”), have shown how blue bonds can help fund marine conservation efforts, while meeting economic goals[5]. As more institutions explore these instruments, Latin America can offer important lessons on what works, what doesn’t, and how legal and financial structures can be designed to contribute towards ocean and marine-focused goals. In this article, we will also look at how the Asia Pacific region is leading the global blue bond market, showcasing initiatives for both emerging market debt reduction and marine sustainability, driven by strong regional dependence on the marine ecosystem, increasing multilateral and NGO involvement in blue finance initiatives, growing interest from regionally based ESG-focused investors, and a region that comprises Pacific and Indian ocean island nation territories vulnerable to climate change. With the right frameworks and partnerships, blue bonds could become a cornerstone of Asia’s sustainable development and climate resilience strategy.

Blue Bond Market Activity in Emerging Countries

Latin America

Since early 2023, Latin America has accounted for nearly half (49.1%) of all global blue bond issuance[6]. Countries like Ecuador, Colombia, Costa Rica and Brazil are increasingly pursuing blue finance. As part of this growing movement, in 2024, the Latin American Stock Exchange (“Latinex”) held its second bell-ringing ceremony for climate finance, celebrating the recent achievements in the listing of thematic and sustainability-linked bonds, including the region’s growing focus on water and ocean conservation projects through capital markets[7].So far, transactions in Latin America have followed two main paths: private sector-led blue bond issuances by commercial banks and sovereign or blended-finance structures, involving public institutions and international partners.

On the private side, BBVA Colombia issued its first blue bond with IFC support to fund coastal conservation. Banco Internacional in Ecuador raised $79 million for sustainable fisheries and aquaculture, and Banco Nacional in Costa Rica issued a bond for marine-coastal initiatives with the backing from IDB Invest. Banco Bolivariano launched a tourism-linked blue bond, the first of its kind[8].

On the public and sovereign side, Belize established a funding scheme that now finances over 35% of its marine protected areas and aims to be self-sufficient by 2026[9]. Similarly, Ecuador executed a $1.6 billion debt buyback and issued a $656 million bond to fund Galapagos marine conservation efforts[10]. These innovative structures have been key examples of how blue finance can be leveraged for environmental and economic impact.

These recent transactions also demonstrate the growing need for DFIs to get involved and contribute to de-risking blue projects and supporting local financial institutions to enter the market. For instance, IFC mobilized capital in the region through a $150 million loan to SABESP in Brazil, a $40 million deal with Banco Internacional, and a $160 million sustainable loan to Produbanco in Ecuador to expand its blue economy initiatives[11].

These early deals are giving other private actors a roadmap for how to structure and enter the blue finance market. Domestic and regional banks are beginning to explore their own blue frameworks, and regulators have started considering mechanisms for identifying and verifying blue finance instruments. In the future, national banks may play a larger role in providing capital to build investor confidence in this emerging space[12]. Moreover, a more harmonized regional framework may allow for the creation of platforms that facilitate cross-border investment and project pooling[13].

Asia-Pacific

Asia, particularly Southeast Asia, is emerging as a critical hub for blue finance due to its deep reliance on marine ecosystems for food security, livelihoods, and climate resilience. However, the region faces severe challenges: (i) overfishing and declining fish stocks (e.g., catch rates in the South China Sea have dropped by up to 75%); (ii) marine biodiversity loss, with nearly 60% of regional shark and ray species threatened; and (iii) underfunded conservation efforts, with less than 3% of Southeast Asia’s national seas formally protected. Coastal economies like Indonesia, the Philippines, and Fiji are beginning to explore blue finance to fund sustainable fisheries, climate adaptation, and marine biodiversity preservation

Globally, the blue bond market is still nascent but growing rapidly. Since the first issuance by Seychelles in 2018, over $5 billion in blue bonds have been issued, with a 92% compound annual growth rate between 2018 and 2022. In Asia, there has been a surge in blue finance instruments, and good examples of this include:

Small-scale Fisheries Impact Bond (“SFF Bond”): Launched in Jakarta in 2025, the SFF Bond is a world-first in financing sustainable small-scale fisheries. Developed by Rare, a global conservation organization, with support from the UK’s Blue Planet Fund (financial support), the Ocean Risk and Resilience Action Alliance (structuring and coordination), the Pershing Square Foundation (initial feasibility funding) and the UK Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs UK (outcome funder). The SFF Bond supports community-led fisheries management, aiming to revitalize ecosystems while improving local livelihoods and sustainability in small-scale fisheries. The bond uses an outcomes-based financing model, where investors are repaid based on verified ecological and social results—such as improvements in coral reef health and biomass recovery. It focuses on establishing Managed Access with Reserves in Southeast Sulawesi, empowering artisanal fishers and enhancing marine biodiversity.

Indonesia Coral Bond: This innovative bond was launched in 2024 and channels capital into coral reef restoration and marine biodiversity protection. As an outcome-based bond, it also aims to enhance ocean biodiversity and improve the management of over 5 million hectares of marine protected areas in Indonesia. It builds on the model of the World Bank’s earlier Wildlife Conservation Bond and is structured to link investor returns to measurable improvements in coral reef health and management effectiveness. It was issued by the World Bank in collaboration with the Government of Indonesia, the Global Environment Facility, the International Union for Conservation of Nature, and a commercial bank. The bond leverages blended finance to attract private investors, while ensuring ecological outcomes.

Asian Development Bank (“ADB”) Blue Bond: The ADB Blue Bond has had multiple issuances since it was first launched in 2021 and has been deployed to fund projects in Asia-Pacific that support marine biodiversity, sustainable fisheries, and coastal resilience, including coral reef protection in the Philippines, mangrove restoration in Indonesia, and sustainable aquaculture in Vietnam.

Blue Alliance Impact Loan Facility: Whilst this is a debt facility rather than a blue bond, it forms an important part of the overall blue finance package in Asia. The facility provides concessional loans to projects that align with blue economy principles. The Blue Alliance Impact Loan Facility was established by Blue Alliance in partnership with BNP Paribas (through its Impact Investment team) and the Global Fund for Coral Reefs, co-led by the United Nations Capital Development Fund. The facility is designed to provide impact loans to support reef-positive businesses operating in and around Marine Protected Areas (“MPAs”). It combines grants and concessional loans to fund early-stage enterprises in sectors like responsible ecotourism, community-based aquaculture, blue carbon credit, and sustainable fisheries. The goal is to generate sustainable income streams for MPA management, while addressing local ecosystem threats and supporting coastal livelihood. In practical terms, it has supported initiatives ranging from mangrove restoration to sustainable aquaculture across Southeast Asia.

Debt-for-nature swaps. A recent example of a debt of nature swap was the US-Indonesia agreement. In a landmark agreement, the U.S. and Indonesia executed a debt-for-nature swap that redirects debt repayments into marine conservation programs. Essentially, this means that the creditor (in this example the US Government), agrees to reduce or cancel part of a developing country’s debt, and the debtor country (in this example Indonesia), commits to using the equivalent value of the forgiven debt for environmental purposes. A debt agreement is established outlining the terms of the swap. Funds are channelled into a conservation fund, often managed by a local trust or NGO, which will support environmental projects such as marine conservation, reforestation, or biodiversity protection. These projects deliver both long-term ecological and social benefits, while easing the country’s debt burden. This model is now being explored by other nations in the region.

These instruments all aim to blend philanthropic capital, public funding, and private investment to scale marine protection and sustainable ocean use. China has also piloted blue bond programmes with issuances from the Bank of China and China Development Bank, aimed at funding marine pollution control, port decarbonization, and sustainable aquaculture.

Blue Bond Market Activity in Emerging Countries

Blue bonds are gaining attention, but the legal and regulatory framework still isn’t fully in place. In Latin America and Asia-Pacific, most deals so far have needed support from MDBs and DFIs to help with structuring and risk-sharing. In emerging market jurisdictions, sponsors, investors, MDBs, and other market participants face the following legal and regulatory challenges:

- Lack of standardized national frameworks: Many jurisdictions lack specific legal frameworks for blue finance. There is no universally accepted framework for what qualifies as a “blue” bond and this can create confusion among issuers and investors. It is often the role of legal advisors like Trinity to align local practices with international frameworks, like ICMA’s Green Bond Principles[14].

- Defining eligible use of proceeds: Currently, there is no consensus on what qualifies as a “blue” activity[15]. This lack of clarity can create uncertainty for issuers, investors and other market participants. This absence of a universally accepted definition of a “blue” bond or “blue” loan can lead to “blue-washing” (i.e. mislabelling of bonds as environmentally beneficial). Legal advisers, finance parties, issuers and interested parties need to work together to define and justify the eligibility of specific projects, such as sustainable fisheries, wastewater treatment, or coastal tourism, under SDG 14. Without a clear justification, transactions may struggle to meet disclosure expectations, avoid blue-washing concerns, and secure support from MDBs and DFIs.

- Risk-sharing mechanisms: Transactions backed by guarantees, like the 2023 IFC-backed electric ferry in Uruguay, require detailed discussions on how to divide and allocate risk in the contract[16]. These deals often involve multiple public and private parties with different expectations and risk tolerances. Agreements must be carefully drafted to define responsibilities and assumption of risks, address potential consequences if targets aren’t met (i.e. in the event of underperformance issues), and ensure the guarantee is enforceable under local law.

- Cross-border legal issues: Some bonds issuances, like Ecuador’s Galapagos deal, involve marine areas beyond national jurisdiction[17]. This can make it difficult to determine which legal frameworks apply, who is responsible for oversight, and how environmental commitments will be monitored and enforced. In such cases, including clear contractual provisions assigning obligations (e.g. reporting, third-party verification) will be key.

- Disclosure and reporting obligations: Currently, due to the lack of binding regional standards, issuers such as Banco Bolivariano, in the Latin American context, are expected to create their own reporting frameworks in order to inform investors and MDBs about environmental impacts[18]. This frequently requires close collaboration with investors and MDBs to reach consensus on important metrics, timelines, and formats. For first-time issuers in particular, the absence of consistent criteria may result in delays and higher transaction costs.

- Coordinating with multiple stakeholders: In cases like Belize’s funding scheme, legal teams must ensure alignment across public authorities, MDBs, and project developers to enforce environmental commitments[19]. In Indonesia, aligning national marine policies with local community needs and international investor expectations has proven difficult. This results in delays in project rollout and difficulty in meeting agreed milestones. Local communities are often not adequately consulted or involved in project design, and as a consequence in coastal areas of the Philippines and Vietnam, fishing communities have resisted conservation measures that restrict access to traditional fishing grounds. The outcome is social pushback, reduced compliance, and reputational risks for issuers.

- High Costs and lack of capacity: Structuring blue bonds—especially those involving blended finance or outcome-based models—can be complex and expensive. Smaller countries or projects may find it financially unfeasible to issue blue bonds – and in regions like Asia where blue bonds would ideally be deployed to support environmental initiatives in small Pacific and Indian islands – costs can make this a disproportionately expensive form of funding. Ocean-related projects are also vulnerable to climate change impacts like sea-level rise, coral bleaching, and extreme weather, which also affect project viability and investor confidence, with impacts on pricing. Many potential regional investors are unfamiliar with ocean finance and its risk-return profile, and emerging market countries often lack the technical expertise and institutional frameworks to design, monitor, and report on blue bond projects which are needed to attract investors. This further impacts the potential pool of investors in an already limited market. Taking Asia as an example, this means there is only a small pipeline of viable projects in the region, thus even when capital is available, it may not be deployed effectively due to lack of viable opportunities. In Malaysia and Thailand, many promising initiatives lack feasibility studies, business models, or clear revenue streams.

Recent transactions have illustrated a recurring set of legal and regulatory issues, including fragmented ESG requirements, uncertainty around blue-eligible activities, and cross-border cooperation challenges. Legal and financial advisors who understand both the financing structures and policy environment can help market participants translate blue and ocean-related environmental goals into enforceable contracts; define eligibility and impact criteria; define risk-sharing structures; and ensure compliance with local and international regulation. This support is especially critical where public and private actors are working together in emerging market jurisdictions under unique and often innovative structures.

Conclusion

Blue bonds are still a small part of the sustainable finance market, and Latin America has emerged as an early leader in both innovation and volume, with Asia also pushing ahead as a leader of innovative forms of blue bonds and other forms of blue finance. Transactions in Belize, Ecuador, Colombia, and Costa Rica, supported by institutions like IFC and IDB Invest, show that the model works when combined with strong structuring support and de-risking tools[20]. In Asia, the creation of outcome-based bonds, sustainability based blue loan facilities, and the debt for nature swaps have been both impactful and innovative and are creating a blueprint for the protection of marine environments and the marine economy. There is a clear MDB and DFI mandate to create viable blue financing transactions, with an expected US$90 trillion allocation in infrastructure over the next decade including investments largely in or around coastal regions[21].

The blue finance market is nascent but exciting, and there is enormous scope for legal and financial advisors with experience in development finance to design credible, bankable frameworks, de-risk the transaction process, and ensure regulatory alignment from structuring through to impact reporting.

[1] International Finance Corporation, Blue Finance, IFC, https://www.ifc.org/en/what-we-do/sector-expertise/financial-institutions/climate-finance/blue-finance (last visited June 2, 2025).

[2] IDB Invest & U.N. Global Compact, supra note 1.

[3] IDB Invest & U.N. Global Compact, supra note 1; International Finance Corporation, supra note 2.

[4] IDB Invest, Business Trends in Marine Conservation: Unlocking a Sustainable Blue Economy in Latin America and the Caribbean (June 2023), https://idbinvest.org/en/publications/business-trends-marine-conservation-unlocking-sustainable-blue-economy-latin-america.

[5] Id., Aliya Shibli, Why Latin America Is Capitalising on the Nascent Blue Bond Market, The Banker (Apr. 4,2024), https://latinfinance.com/topics/esg/2024/08/15/blue-bonds-gain-ground-in-latam-as-climate-finance-solution/.

[6] Aliya Shibli, supra note 6.

[7] Latinex, Latinex Celebrates Its Second Bell Ringing for the Climate: New Milestones in Emissions Themes and Sustainability, LATINEX (November 18, 2024), https://www.latinexbolsa.com/en/news/latinex-celebrates-its-second-bell-ringing-for-the-climate-new-milestones-in-emissions-themes-and-sustainability/.

[8] LatinFinance, Blue Bonds Gain Ground in LatAm as Climate Finance Solution (Aug. 15, 2024), https://latinfinance.com/topics/esg/2024/08/15/blue-bonds-gain-ground-in-latam-as-climate-finance-solution/

[9] IDB Invest, supra note 5.

[10] Rafael Janequine, Bryan Popoola & Joydeep Mukherji, Latin American Sustainable Bond Issuance To Rise in 2024, S&P Glob. Ratings (Feb. 27, 2024), https://www.spglobal.com/ratings/en/research/pdf-articles/240227-sustainability-insights-research-latin-american-sustainable-bond-issuance-to-rise-in-2024-101593792.

[11] International Finance Corporation, supra note 2.

[12] Aliya Shibli, supra note 6; IDB Invest & U.N. Global Compact, supra note 1.

[13] IDB Invest & U.N. Global Compact, supra note 1.

[14] IDB Invest & U.N. Global Compact, supra note 1; International Finance Corporation, supra note 2.

[15] International Finance Corporation, supra note 2.

[16] LatinFinance, supra note 9; International Finance Corporation, supra note 2.

[17] IDB Invest, supra note 5; Rafael Janequine, Bryan Popoola & Joydeep Mukherji, supra note 11.

[18] Aliya Shibli, supra note 6.

[19] IDB Invest, supra note 5.

[20] IDB Invest, supra note 5; Aliya Shibli, supra note 6.

[21] Aliya Shibli, supra note 6.

Our Experts

Fiona Gulliford – Partner, Head of Asia-Pacific

Sonia Forcada, Associate, Washington D.C.

***

Democratic Republic of Congo – Amendment to the Electricity Law

The Democratic Republic of Congo (“DRC”) is home to approximately 105 million inhabitants, the vast majority of whom still lack access to electricity. The overall electrification rate stands at around 9%, rising to 30% in urban centres but falling to only 1% in rural areas.

DRC’s national electricity company, Société Nationale d’Electricité S.A. (SNEL), which is the main operator of the transmission and distribution networks operates approximately 7,000 kilometres of high-voltage lines for a country covering 2,345,000 km2.

Further, due to historical and economic reasons, SNEL’s transmission and distribution networks are concentrated around regions with mining projects, particularly in the former Katanga province (with a main transmission line of 1,700 kilometres connecting the Inga hydropower plants to the cobalt-rich Kolwezi region) and in the Kivu region. As a result, numerous provinces and urban areas, some inhabited by several million inhabitants, are not connected to SNEL’s transmission network.

In recent years, several initiatives have aimed at developing “metro-grids” (i.e., mini-grids designed to supply densely populated areas not connected to the national grid).

The cornerstone of DRC’s electricity sector legal framework is Law No. 14/011 dated 17 June 2014 as supplemented by Law No. 18/031 dated 13 December 2018 (the “Electricity Law”).

The Electricity Law has recently been amended through Ordinance-Law No. 25/025 dated 5 February 2025, amending the Electricity Law (the “2025 Ordinance”).

Aiming at simplifying the implementation of electricity projects in rural and peri-urban areas, the amendments to the Electricity Law are particularly relevant to mini-grids, as the main innovation of the 2025 Ordinance is the creation of an “isolated mini grid licence for rural and peri-urban areas” (the “Isolated Mini Grid Licence”).

Such Isolated Mini Grid Licence allows its holder to carry out electricity generation, transmission, distribution and sale activities under a single licence (rather than having to obtain both a distribution concession and a production licence or concession, or to operate under a public service concession).

However, the legal regime applicable to an Isolated Mini Grid Licence is not detailed in the 2025 Ordinance, raising some key issues:

- Procurement Procedure:

The 2025 Ordinance provides that concessions and licences are to be awarded in accordance with a decree from the Prime Minister, setting forth the award procedure for electricity sector contracts.

Such decree has not yet been published. It is expected to be an implementing decree that will specify the licence and concession award procedures and likely and likely replace the current Decree No. 18/052 dated 24 December 2018. setting This sets forth the conditions for operator selection, and for the award, amendment, and revocation of concessions, licences and authorisations in the electricity sector.

- Territorial Scope:

The 2025 Ordinance introduces the Isolated Mini Grid Licence for “rural and peri-urban areas” without providing a definition of these terms. Hence, it is unclear whether an Isolated Mini Grid Licence could be used in the context of a “metro-grid”.

Given the various metro-grid projects currently under development in DRC, it would have been appropriate to clarify the territorial applicability of the Isolated Mini Grid Licence regime and to ensure that urban areas are not excluded.

- Competent Authority:

The 2025 Ordinance provides that the Isolated Mini Grid Licence is granted by the “competent authority”, following the approval of the electricity regulatory authority, namely Autorité de Régulation du Secteur de l’Electricité (the “Regulatory Authority”), but does not specify whether this refers to the central government authority or a provincial authority.

For generation and transmission concessions only, the 2025 Ordinance clarifies that the central government is the competent authority for generation projects with a capacity of 5 MW or more, and for transmission lines operating at 36 kV or higher.

For both bankability reasons (limited creditworthiness of provinces) and practical implementation (provinces may lack experience with complex project finance contractual structure), sponsors and lenders may prefer that Isolated Mini Gird Licence be issued by the central government.

- Duration of an Isolated Mini Grid Licence:

The 2025 Ordinance does not specify the term of an Isolated Mini Grid Licence.

It would be advisable for the implementing decrees of the 2025 Ordinance to specify a sufficiently long duration to allow investors to recover their investments — or even to omit a maximum term, as is the case with generation concessions under Article 52 of the Electricity Law.

- Public Domain:

A combined reading of Articles 46 and 66 of the Electricity Law suggests that generation and distribution activities performed on State public domain must be carried out under the concession regime.

However, the 2025 Ordinance introducing the Isolated Mini Grid Licence does not specify whether project sites located on State public domain or State private domain are treated differently.

In addition to introducing the Isolated Mini Grid Licence, the 2025 Ordinance includes several other noteworthy changes:

- Compliance certificate:

Under Article 29 of the Electricity Law, the commissioning of infrastructure, particularly for electricity generation and distribution, is subject to obtaining a compliance certificate delivered by the Regulatory Authority.

The Electricity Law failed to provide a timeline for the Regulatory Authority to issue the compliance certificate, potentially leading to unjustified delays in commissioning.

To address this gap, and similarly to the approach taken by Ministerial Order No. 081/CAB/MIN/ENRH/18 dated 27 December 2018 (relating to the general specifications for electricity sector activities), the 2025 Ordinance now establishes a clear timeline: the Regulatory Authority, assisted by an independent expert, shall perform all necessary tests and issue the compliance certificate within one (1) month from the compliance certificate application. If no response is given within that timeframe, the certificate is deemed granted and must be issued within ten (10) days following the expiry of the one-month period.

- Electricity Supply for Local Communities:

Article 54 of the 2025 Ordinance introduces a new obligation requiring that any holder of a generation concession or any self-producer must allocate at least 10% of their production for commercialisation to local populations and surrounding communities.

A ministerial order is expected to further detail the specific conditions for implementing this new requirement.

Our Experts:

Pierre Bernheim – Partner

Alexis Giroulet – Senior Associate

***

Trip Report – Shanghai

We were invited by our friends at Fangda Partners to take part in an “Africa Week” event hosted by the firm and inspired by the still-growing interest in China of investing in Africa. We also took the opportunity to meet with several private and state-owned entities with current and proposed investments on the continent across a wide range of sectors.

It was a pleasure to present, discuss and exchange with representatives of the Chinese mining and energy business community. For “Africa Week”, we led presentations and sessions on renewable power, mining, oil and gas and ESG and Business Human Rights (with Pierre Bernheim joining remotely from Paris for the renewable power session). We covered a variety of topics, including deal structuring, risk management and bankability, as well as crisis management, settlement, mediation and international arbitration, local content and ESG — including China’s new ESG rules based on the United Nations Guiding Principles.

While the sessions were primarily focused on Africa, there was also strong interest in other regions, allowing us to draw comparisons based on our experience in the Middle East, Asia and beyond.

We were particularly impressed by the growing interest of Chinese companies in long-term sustainable investment in Africa. The general consensus was, whilst there are issues that need to be carefully navigated (and documented through fair, robust documentation), Chinese led investment in Africa can have mutually beneficially outcomes for all stakeholders involved.

We received an incredibly warm welcome everywhere we went and are deeply grateful to Monica Sun and Jie Li (Fangda Partners), Crystal Lo (ON Legal Marketing), and all those who hosted us so kindly.

We look forward to continuing the conversation!